COVID-19: do we need to reimagine the purpose of school inspections?

20 Jul 2020 | Professionals

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis that has presented significant challenges to education systems. These have included whole system shutdown of schools, the cancelling of national examinations and a shift to distance and digital learning. For the time being regular school inspections have stopped in many countries. Given that it is not ‘business as usual’, should we ‘inspect’ schools, and if so, for what purpose? This question was discussed in a webinar with 35 delegates from Inspectorates of Education in 12 countries, with further validation of the findings presented in an online participant check. The outcomes of the webinar indicate a change in inspection purpose where, during the pandemic and school closures, ‘support and improvement’ and ‘liaison’ were at the forefront of the work of Inspectorates of Education. This paper presents examples of how these functions were implemented between March and July 2020.

Prof. Ehren

Prof. Chapman (Chris.Chapman@glasgow.ac.uk)

Prof. Montecinos (carmen.montecinos@pucv.cl)

18-07-2020

Please cite as:

Ehren, M.C.M., Chapman, C., and Montecinos, C. (2020). COVID-19: do we need to reimagine the purpose of school inspections? ICSEI internal report.

The authors like to thank Lynda Frazer, Doris McWhorter and Graham Donaldson for their support and advice in organizing the webinars.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis that has presented significant challenges to education systems. These have included whole system shutdown of schools, the cancelling of national examinations and a shift to distance and digital learning. For the time being regular school inspections have stopped in many countries. Without inspection and assessment there is a lack of: standardized information on whether and how pupils are learning and how they are currently being educated; how parents are coping with home-schooling; to what extent and how schools are teaching online and how they are supporting parents in their new role as ‘teachers’. A good understanding of whether and how learners are taught – either through home-schooling, online teaching or blended modes of learning- and where this is– or isn’t– working well enables a sharing of good practice across the country. Additionally, it can highlight issues of equity to which educational policymakers and practitioners should respond.

When schools are (partially) closed, ‘quality of education’ takes on a different form and meaning and roles and responsibilities of those tasked with teaching, learning and leading changes.

Given that it is not ‘business as usual’, should we ‘inspect’ schools, and if so, for what purpose?

This issue was discussed in a webinar with 35 delegates from Inspectorates of Education in 12 countries, with further validation of the findings presented here in an online participant check. More specifically, the questions the webinar explored were:

- Do we need to rethink the purpose of inspection during and (immediately) after the pandemic?

- How can Inspectorates of education be relevant to schools, parents, learners and policy-makers in a time of school closure and when schools are (partially) reopening?

School inspections are widespread and can take on many forms. SICI, the Standing International Conference of Inspectorates of Education currently has 39 members in Europe; in other parts of the world, school inspections are also termed ‘quality reviews (in the US) or supervision (parts of Africa), where agencies performing those tasks often also have other responsibilities in school/system evaluation, such as in advising on national curricula or developing and administering national and international student assessments.

Here we understand school inspections as:

‘External evaluations of schools, undertaken by officials outside the school with a mandate from a national or local authority’.

Regular visits of schools are typically an essential part of school inspections to collect information about the quality of the school, check compliance to legislation and/or evaluate the quality of students’ work (e.g. through observations, interviews and document analysis). In a pandemic, when schools are closed, such visits are no longer possible however and ‘collecting information’ will need to be done in other ways and/or on other topics.

Also, what ‘educational quality’ means has drastically changed. Schools have moved to online teaching, or (when partially opened) to blended modes of face-to-face instruction and home-schooling. Teachers have had to think about new ways to assess learner progress, examine whether students meet exit requirements for graduation, and monitor the well-being and safety of learners, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. With some or all of the schooling now taking place at home, parents are tasked with supporting their child’s learning and the educational partnership between parents and schools needs to be carefully managed to ensure student learning.

Schools also require a different type of leadership and management, where school principals need to engage with their staff off-site and create a sense of community while also ensuring a school-wide approach to online learning. They need to equip teachers with the professional skills to teach online or in blended modes and to engage with parents, particularly when there is an expectation of home-schooling. Furthermore, when schools reopen, school leaders have to work in collaboration with other local agencies to prepare the school building and instructional time table to enable social distancing and ensure schools are safe places for parents, teachers and learners to go to.

When schools are (partially) closed, ‘quality of education’ takes on a different form and meaning and roles and responsibilities of those tasked with teaching and learning changes.

How are inspection agencies adapting to this new reality? Has the purpose of inspection changed during and (immediately after) the pandemic? And are these changes temporary or indefinite?

COVID-19: repurposing inspection to support and liaise

At the start of the pandemic when schooling was suspended, there was widespread understanding for the immense efforts undertaken by teachers and head teachers to develop online/remote teaching and learning. In this initial stage, schools were considered fragile, where goodwill and strong collaboration was needed to move entire education systems to a new way of working. Inspection, checking and control was not considered appropriate at this time. Most schools have now somewhat stabilized their online teaching, although in some countries, challenges remain in students’ access to online teaching/remote learning: some families don’t have computers/laptops (or perhaps only one laptop that needs to be shared during the day) or don’t have (good) access to internet. In some families, tensions and levels of stress are high (due to being confined to small spaces, because of financial insecurities or COVID-related mortalities), impairing on children’s learning and well-being. These concerns and understanding the quality of the schooling provided are at the forefront of Inspectorate’s of Education current work.

During our webinar we presented participants with the following three purposes of inspections commonly used to describe the function of inspection (adapted from De Grauwe, 2007; Davis and Martin, 2008):

- The first purpose is to control and ensure compliance with statutory regulations, for example when Inspectorates of Education check whether schools have a behavioural policy in place, or meet safeguarding requirements. Standards used to check for compliance tend to be assessed on a ‘yes’/’no’ scale.

- The second purpose is to give support and advice on the improvement of school processes and learning outcomes. Inspectors use their professional judgement and expertise to assess the quality of teaching and the school (leadership/organisation) and their feedback on potential weaknesses is expected to lead to positive change.

- To third purpose is to act as a liaison agent:

- between the top of the education system and the schools by informing schools of decisions taken by the centre, and to inform the centre of the realities at school level,

- between schools and stakeholders when identifying and spreading new ideas and good practices between schools,

- establishing good linkages with other services involved in quality development such as pre- and in-service teacher training, curriculum development, preparation of national tests and examination. These roles can focus either on the individual teacher, on the school as a whole, or on the (monitoring of the) entire education system.

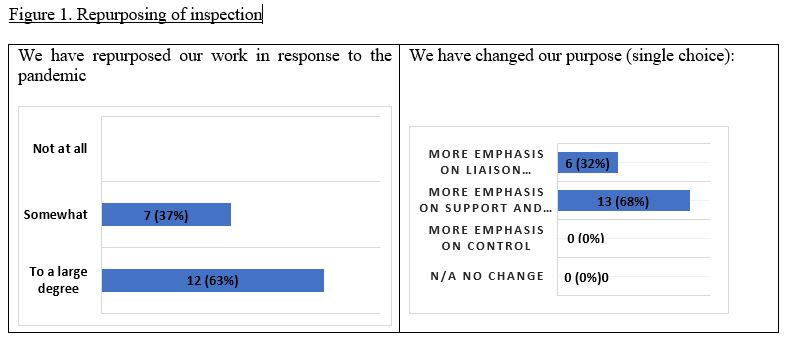

In a poll, we asked participants whether and how their Inspectorate has repurposed its work in response to the pandemic and the widespread closure of schools. Responses from 19 participants from 12 countries (ICSEI webinar 17 June 2020) show that all the Inspectorates of Education acknowledge a change in purpose where ‘support and improvement’ and ‘liaison’ are now at the forefront of their work:

Suspension of regular inspection and a change in the ‘object’ of inspection

Participants discussed and shared examples from their inspection agency on how purposes have (temporarily) changed, how support is provided to various stakeholders and what their current liaison function involves (see appendix 1). As schools are closed, the object of the inspection – which is generally the school- has completely changed and is no longer just a physical reality, reemphasizing its role as a community where teaching and learning is a shared practice of school staff, parents, and learners. During regular school visits, the emphasis tends to be on the physical reality of the school, even though the encounter is mostly with the school principal. Some Inspectorates of Education emphasized an increased need to also engage with parents, teachers and learners to really understand what good quality teaching (remote/blended) is for different groups of learners, and some Inspectorates are including these groups in their monitoring and/or support. The Hamburg Inspectorate for example surveys parents and learners to understand their engagement in online learning, while Estyn, the Welsh Inspectorate, has initiated a stakeholder group of inspectors who are also parents and home-schooling their children to understand parents’ experiences. Education Scotland has developed a set of activities for parents and teachers to use in home-schooling, online learning and to ensure children’s well-being under lock-down.

More emphasis on support of government and schools

The support provided by Inspectorates of Education is however predominantly of schools and (national) governments and linked to the liaison role of inspection (discussed below).

Support of government

Support to government (e.g. Wales, Scotland) includes the (co)development of strategies and policies to ensure all learners (particularly in vulnerable situations) have access to remote teaching and learning and the implementation of these strategies. In Scotland, HMI also supports the government in scrutinizing plans of local authorities regarding the reopening of schools and implementation of blended learning, assessing the extent to which plans are equitable and whether the maximum number of learners are provided with face to face schooling within the restrictions of social distancing. The support is informed by the monitoring work of the Inspectorate and their understanding of challenges in the system.

Support of schools

At the start of the pandemic, the support of schools was mostly pastoral care for head teachers, in the form of phone/video calls. In Flanders for example, inspectors were assigned to a group of 15-20 schools as a ‘liaison inspector’ and they have regular contact with head teachers to understand how they cope. Information from the phone calls on challenges schools face is reported back to national government. Schools are also invited to contact their liaison inspector when they need help. Similar arrangements were put in place in Chile and Wales with engagement calls of schools at the start of the pandemic. Chile is using a three-staged approach with schools where initial contact and pastoral care is followed up with the sharing of tools for schools to use in online learning and checking the usefulness of these tools.

The type of support evolves over time as schools reorganize their work, open part-time and more information on the consequences of school closures becomes available, such as about potential learning loss of disadvantaged pupils, concern over student well-being and their development of socio-emotional skills, and the –lack of- quality of implemented approaches of remote/blended forms of teaching and learning. After an initial ‘crisis’ phase, some Inspectorates of Education started to provide schools with instructional materials (including for parents to use in home-schooling, or working with broadcasting companies in developing instructional TV programmes, such as in Mexico and Chile), and/or wider guidance of new modes of teaching and learning and how to organize an optimal schooling environment. In Chile, schools were provided with self-evaluation surveys to measure student well-being and learning progress, while Education Scotland developed activities for homeschooling, particularly for learners in disadvantaged areas, which don’t require access to technology.

Whether schools accept and engage with the support depends on how they view the Inspectorate. A number of participants talked about how an ‘inspection badge’ comes with an understanding of control and a level of anxiety. In Wales, the repositioning towards a more supportive inspection is specifically managed through targeted messaging, such as YouTube videos of the chief inspector. Education Scotland’s regular framework (PRAISE) include a set of guidelines for inspectors on how to communicate with schools in a supportive manner.

Some Inspectorates of Education (Wales, Chile) initially targeted schools in an inspection category (special measures/insufficient) for initial support and moved to a wider sample once these schools had been contacted.

More emphasis on liaison between government and schools

Liaison at the time of school closure concentrated on informing government on how schools are moving to remote teaching/implementing blended models and where there are problems. Some Inspectorates also share practice across schools. Most of the monitoring is through surveys, administered online or by phone calls to school principals. Only in Hamburg, Germany has the Inspectorate sent out surveys to parents and teachers, but these groups tend to be hard to reach, particularly when the Inspectorate of Education is unknown by the general public and/or teachers/parents receive surveys by (many) other organisations.

Reports from such monitoring are shared with national government to inform a more coordinated response to the pandemic and organize support of schools, such as by providing guidelines on how to teach online or assess student learning remotely (e.g. Chile and Malta). A quick and effective response to the findings from the monitoring reports is enabled when the Inspectorate of Education has good collaborative relationships with major stakeholders across the system, such as the Ministry, and (head) teacher unions. Constructive collaboration with these partners ensures that solutions are found and quickly implemented instead of spending valuable time on mediating conflict (e.g. on whether and how to reopen schools, or whether teachers have to teach synchronously or asynchronously when also having to homeschool their own children). The legislative remit of the Inspectorate of Education and whether the agency is able, or allowed to operate outside its regular framework, such as in offering support and guidance and evaluating other quality standards, is relevant here. In Flanders for example, the education system is structured to separate the monitoring and support function across different organizations, preventing the Inspectorate to provide any guidance or advice to schools. In Wales, emergency legislation was put in place to allow schools to operate outside the regular regulatory framework; Estyn however already had a broad inspection framework in place which allows them to monitor these changed operations.

Some participants explained how the monitoring reports initially messaged strong support of schools and an empathic tone of voice (e.g. in the Netherlands) but now move to a more investigative approach when the initial sense of crisis past and when widespread variation in the quality of provision was indicated (and signaled in other media). Various countries (Chile, Wales) are currently considering how to share good practice from such monitoring between and across schools.

Building on existing structures and networks to support and monitor

In their support and liaison role, Inspectorates of Education build on existing networks and collaborative structures. Existing networks and structures are for example head teacher boards in Wales who provide feedback on inspection frameworks and reports and who share insights from inspections with their own local networks of head teachers, or regional inspection offices working with local authorities in ensuring schools are supported in moving to online/blended modes of teaching, learners have access to laptops and/or school buildings and teaching schedules are set up for social distancing (Wales, Scotland), or where inspectors work with local school improvement networks (Wales). These networks and structures are, in addition to coordinating support, also used to understand local needs and challenges (e.g. limited access to internet and computer facilities in specific areas/for specific groups of learners) and to inform relevant authorities about where additional arrangements need to be put in place. In Malta, inspectors for example joined professional development sessions of teachers, organized by schools to understand the changes schools were making.

No change

Where there is no change in purpose (e.g in Portugal), the Inspectorate would already have a (somewhat wider formulated) remit which fits the current situation; e.g. ‘ensuring students’ needs are met’ and/or where there is emergency legislation with allows schools to adopt their practice to meet learners’ needs (Wales) and for a temporary change in inspection approach. Having a broad framework allows for a monitoring of how schools adapt to remote teaching (e.g. Wales). Also, where Inspectorates of Education are not required to give graded judgements (Wales, Malta) they can give a narrative assessment to capture current changes in teaching practice.

A summary description of each country can be found in appendix 1.

Changes in the purpose of inspection: temporary or permanent?

‘Everything is changing as we go’ is how one of the participants summarized the current situation and how Inspectorates of Education are having to be agile and flexible in their response to the pandemic. How temporary or permanent are the changes described above?

Some of the participants explained how the emphasis on support and liaison is a continuation of a strategy that was already initiated before the pandemic. Scotland and Wales for example already had, or had started to develop a more supportive approach and are strengthening this during the pandemic. In other countries, the change is however a clear break from the past, such as in Flanders and Chile where Inspectorates of Education did not have a strong supportive role, or where standards did not allow for an evaluation of current practices of online/remote learning, and/or monitoring how schools are implementing such models. Whether these changes are permanent is unknown and likely to vary across countries.

Some of the participants (e.g. England) expect a return to normal with inspections on the regular framework. The argument would be that the framework is based on a well-researched framework which includes evidence-based standards on school quality and improvement and this is what schools need to focus on. These ‘regular’ frameworks are also the outcome of long processes of consultation, trial and testing and are set in legislation where current standards to respond to the pandemic have been put in place without much scrutiny, consultation or rigorous research.

A number of participants expect a more permanent change in inspection purpose, arguing that the current crisis is an opportunity to look at what is in the best interest of learners. Arguments for a repurposing of the inspection function relate to changes in the current processes of schooling which we might want to sustain after the pandemic. ‘Building back better’ is a phrase that is used here and inspections would have a role in allowing and supporting such innovative models. Their frameworks would need to include standards to assess the quality of new models of blended learning and teaching and/or evaluate the quality of partnerships between schools and other stakeholders (including parents). These new and innovative practices can only sustain when Inspectorates of Education are responsive to these developments and incorporate them in their frameworks.

Portugal, Malta and Wales have therefore started to think about/develop new standards for further monitoring of the quality of online/blended modes of teaching. These standards (in Malta developed in collaboration with the Ministry of Education) may be included in regular inspections when schools (partially) reopen, at least until schools continue to have such models of teaching.

Inspectorates of Education may also be forced to change their purpose, particularly when schools are now experiencing a more supportive and low-stakes inspection function where no judgemental grades are given (e.g. Chile), when inspectors liaise more closely with schools and build close relationships (Flanders) and schools simply don’t accept a high-stakes, judgemental approach. Inspections that are considered to be an ‘administrative burden’ are expected to lose their legitimacy when schools have to spend all their time and resources on ensuring a high quality online learning/blended modes of teaching and tending to the wellbeing of staff and students. Participants also raised questions about whether the use of summative grades would be fit for purpose and accepted when schools reopen and when schools have to increase their efforts to repair potential learning loss. Grades often get in the way of a good discussion on improvement of schools where the current situation perhaps requires a more substantive process of reflection between schools and inspectors.

Enforced change in purpose may also come from a change in the status and legitimacy of teachers and schools. Their status has increased when the general public and politicians have seen their vital role in the economy during the pandemic. This may change the power dynamic between schools and inspectors and also call for a more supportive approach. On the other hand, when Inspectorates of Education showcase examples of where schools are NOT offering a good quality online/blended learning experience, there will likely be more emphasis on a controlling/judging approach and reduce the status of schools/teachers.

Outstanding questions and where to next?

As the initial sense of crisis has passed in most countries and schools are (partially) reopening, a number of other questions arise:

Inspection standards and what to inspect

When schools reopen in blended modes, inspections may need to assess the quality of these approaches. How to assess the quality of online/blended teaching and learning? Participants also discussed current concerns for learning loss, increasing inequality, issues with pupils’ well-being and development of social-emotional skills, potential burn-out of teachers and head teachers, and an increased need for students to self-regulate their learning and for schools to develop students’ executive skills. Do inspection frameworks need to incorporate standards in these areas? If so, what should they look like? Inspectors particularly know what a high quality lesson looks like in a face to face environment, but what does that look like online?

The balance between school inspection and school self-evaluation

Participants also discussed the relevance of quality assurance and self-evaluation as part of external inspections and how these become ever more important when there are no proven concepts for online/blended teaching and learning. Schools need to be asking and evaluating questions to develop this knowledge and sharing this with peers.

Should the balance between external inspection and school self-evaluation therefore change to motivate schools to further develop their internal quality assurance? Do schools need to engage with other partners to mitigate the consequences of the pandemic and should inspection motivate them to do so? Does there need to be more emphasis on school self-evaluation given the absence of other data for inspection? Can schools evaluate the quality of online/blended learning when there is no strong evidence on what effective models for online/blended learning are?

Parents and inspections and remote data collection

When schools are closed and teaching moves online, other actors (teachers, parents) will hold information on quality of teaching and learning than the sources of information and actors generally interviewed and surveyed for inspection purposes (school leaders/school boards, use of standardized assessment data). These actors are however often hard to reach when schools are closed and Inspectorates of Education only manage to do so when they have strong partnerships with representative organisations and/or have the legitimacy and reputation to ensure a high response rate to email/postal surveys. Interviewing teachers and parents remotely can add value in immediate terms (to understand current practices of online teaching/learning/blended learning and home-schooling) and on the long term (to create more teacher and community involvement).

How to engage parents in inspections and what should their role be given that they are now involved in home-schooling (taking on a role as ‘teacher’) and will continue to be involved in blended models of learning and teaching? Should parents be included in regular inspections, not just as informants of school quality, but perhaps also to understand their contribution to learning outcomes? Should parents be interviewed to understand how schools have involved them or prepared them to take on these teaching responsibilities?

Missing data: tracking system performance

Standardized assessment data are an important element of many inspections, such as in England, Scotland, the Netherlands and Chile. These data are used to schedule inspections of potentially failing schools (in risk-based inspections), but they would also be used to understand school quality and outcomes. How to schedule inspections and assess outcomes when such data is now missing due to temporary cancellations of assessments and exams, such as in the case of Scotland? Annual inspection reports (e.g. the state of education in the Netherlands/England) also provide information on how the system as a whole progresses, reflecting on potential increases in achievement gaps and inequality. How to track the quality of schools and performance of schools over time?

Missing data: parental choice

Inspection reports in some countries (e.g. England, Chile) intend to inform parents’ school choice. Given that there will not be any inspection reports (or league tables based on assessment data), how will parents choose a school? When school choice on the basis of quality and outcomes is absent, does this affect school improvement driven by competition?

A detailed overview of outstanding questions per country is included in appendix 2.

Appendix 1. Country summaries of repurposing of inspection

| Country | Current purpose of inspection | Clarification |

| Netherlands | Focus on liaison |

Schools closed mid-March, but primary schools have now fully reopened and secondary schools partially (allowing for social distancing; students attending school 1 to 2 days a week on average) where each school decides on how to be open. A second COVID monitoring is currently being planned for end of June which will be more investigative and less pastoral (given the observed large variation in what schools are offering); the report won’t include graded judgements but will include qualifying statements, less empathetic compared to the first monitoring report and following the approach of regular thematic inspections. |

| Germany (Hamburg) | Focus on liaison | Primary schools are now fully open, while secondary schools are open for 2/3 days a week. Germany suspended regular inspection until January 2021. The Inspectorate surveyed students, parents and teachers (16-19 June 2020), first results indicate parents are experiencing most problems. The survey of parents was initiated after, and in collaboration with a parent organisation which initiated a survey to parents with a high response rate (n = 3000). The Inspectorate contacted them to do a joint follow-up, part of the wider monitoring with students and teachers. Getting a good response to inspection surveys is problematic as the inspection agency is not widely known and parents receive many questionnaires now. |

| Chile | Focus on support |

Schools have been closed for 3 months and the expectation is that the pandemic has not yet reached its peak so schools will be closed for at least 2 more months. Regular inspection is suspended for the foreseeable future. The 3-stage approach, implemented when schools closed, includes contacting schools via phone/video calling (now contacted 400 schools): 1) the first call is about checking in and asking how principals are doing. 2) the second call is to offer targeted guidance and support (including nationally developed tools for remote learning), 3) the third call is to follow-up and to check which tools were used, how relevant these were and what other practices were developed by the school. The agency has (in April when schools were expected to reopen soon) developed a self-evaluation survey for schools to assess learning progress and socio-emotional skills of children; schools will be asked to administer these when they reopen. It allows them to understand how students have developed in these areas during the pandemic and allow students to return to learning. The pandemic has forced the Agency to rethink the purpose of the agency’s work which is to improve education, but this is a political sensitive topic. |

| Malta |

Focus on support (unchanged, somewhat more advisory) and liaison

|

As a country, Malta was never in full lock down, but all schools were closed by mid-March. There were initial issues with the teacher unions when school leaders were asking teachers to teach synchronous sessions online, but a number of teachers were encountering difficulties to do so since they had children at home to take care of (and had to have flexibility in their instructional timetable). Hence, most of these teachers recorded their sessions and this increased their workload. After a period of transition, teachers began collaborating and adapting to online teaching and learning. The ministry set up a website for everyone to share online materials. Subject experts/teachers have uploaded materials and resources for learners, parents and teachers to use. The Inspectorate of Education has not changed purpose as it was always about ensuring student learning, according to their needs. The developmental approach is indicated by the lack of graded judgements, and the provision of an overview of strengths and areas for improvement in a narrative report with a post inspection meeting and a professional dialogue about ways to improve. At the start of the pandemic, the Ministry for Education and Employment, analysed student data to select a sample of 60 (out of 200) schools and administered a survey to these schools about their online digital learning experience. Interestingly all 60 schools stated that they had replicated their in-school teaching model to an online model, instead of rethinking how their teaching can cater for this new reality, particularly for the needs of all learners especially those who are vulnerable. When schools reopen, whatever format of operation they might adopt, the Inspectorate may have an advisory role at a system level on how digital tools can be used more effectively in schools. Some inspectors have also joined webinar seminars organised by the University of Malta and foreign educational institutions to gain further awareness and understanding of what is happening locally and internationally with regards to online learning and teaching. This is part of their professional development learning. |

| Portugal | No change |

No change in the purpose of inspection which is ‘to benefit students’, but how to implement inspections will differ. |

| Scotland | Focus on support and liaise |

Schools were suspended in the middle of March 2020 and break for summer at the end of June until the 11th of August when they will restart with a blended model of home-schooling and in-school learning. Local authorities are now developing plans on how to (partially) reopen schools with blended models of teaching and learning, allowing for physical distancing. HMI will scrutinize these plans for fairness and whether the maximum number of children will receive face to face teaching. The inspection function sits within Education Scotland which also has an improvement and support function and a regional structure to support local authorities and school groups. This regional function has provided support to ensure schooling of children of key workers, to identify vulnerable children and ensure their access to remote learning. The aim is to be responsive and empower all stakeholders to ensure good student outcomes, such as by having regional groups and local teams to support schools in moving to blended learning. Education Scotland is independent of government, but close and good contact with government, particularly to coordinate a response to the pandemic. Teacher unions have also been very supportive of schools and their move towards online/blended learning. Regular inspection is suspended as it is expected to cause anxiety to head teachers and teachers. Inspectors are now tasked with providing support to schools (including pastoral support of head teachers) as well as in providing advice to government. This includes supporting the work of ‘Scotland learn’ in developing blended learning materials and activities that is send out in weekly newsletters to schools/teachers (with suggested activities for their classes and parents (to use in home-schooling their children). Both newsletters include activities for learners aged 5-16 which don’t rely on technology to particularly support learning in disadvantaged areas. The newsletters are available on the ES website and parents/teachers can download it. Inspectors are also part of a national recovery group to develop a plan on how to support schools in recovery. This will include ‘well-being calls’ to schools and developing a framework to evaluate the quality of online learning/blended learning. This is causing much discussion, particularly with unions. The current support work of schools is, to some extent, a continuation of the PRAISE framework that underpins any inspection which includes a set of guidelines on how inspectors should engage with schools (during and after a visit) to support their improvement and compliance to regulation. Special needs inspectors have frequent contact with regular inspectors, particularly to discuss why certain groups of students are not connecting to online/remote learning and how to best engage them. Education Scotland was already developing ideas on how to empower stakeholders through inspection and current crisis emphasizes the relevance of this work. Empowerment would include elements of control and compliance but done with a different tone of voice and approach (more supportive) and more attention to well-being of educators. However, having the stamp of ‘HMI’ and the views and expectations attached to this role sometimes limit the extent to which inspection can be supportive. Crisis allows for an opportunity to repurpose inspection to focus on the needs of learners again as the key stakeholders of education and question whether a graded judgmental approach actually benefits learners as it can have a devastating effect on educators. |

| Belgium (Flanders) | Focus on liaison and (secondary) support |

Schools are currently open for the 6th (final) year, some schools are open for the 4th and 2nd year. Early March at the start of the pandemic each inspector was assigned 15-20 schools and became their liaison inspector. They phone called these schools (school leaders) to ask how they are doing, supporting their well-being and report back concerns to the Ministry of Education to enable them to develop new policy. These school leaders can also contact their inspector in case of problems; inspectors have to be careful in not offering advice as they are not allowed to (see below). This set up is leading to good and closer contact with schools. The Inspectorate has recently visited 200 schools to monitor and gather information about their approach to blended learning, assessments, etc and will report (only) aggregate findings to the Ministry next week (of 22nd June 2020). Inspectors follow safety guideline (wearing facemasks). Inspections suspended since March until 16 June (2020), but no full inspections until December 2020, with research-oriented/special visits between June/September and December (still needs to be decided and also whether this will be on site or remotely, pending infection rates). These visits will be longer, allowing for more in-depth conversations with pupils and teachers compared to ‘normal’ and also have a more research-oriented approach to understand schools’ responses to the pandemic. The Inspectorate is developing six questions that will guide these inspections; questions are currently being developed but one will likely be ‘how has the crisis impacted on student learning, particularly for vulnerable students who have a difficult home situation’. The visits will be used to inform national government of 1) the extent to which students have/are able to access online/remote learning, and when they aren’t: 2) how schools are solving problems with access and engagement. The visits will also inform further development of the inspection framework which was recently renewed but now needs to be adapted to allow inspection in line with health guidelines. Due to freedom of education with a separate support structure for schools through ‘guidance institutes’, the Inspectorate of Education is not allowed to share good practice between schools, only share good practice anonymously. The Inspectorate still needs to decide whether these visits will lead to a graded judgement (as in regular inspections) and have formal consequences for schools who are judged to be failing or whether the main purpose is to monitor/liaise and/or support schools; viewpoints vary within the Inspectorate. Current legislation requires the Inspectorate to give a graded judgement after an inspection visit and share these with national government. Viewpoints on whether current inspections need to control or support also develop over time; 3 weeks ago much focus on support as there was a view that teachers and head teachers are working hard but last week more concern for children’s learning and a stricter tone. There were initial plans to ask schools to write a self-evaluation report in September/October, looking back on schooling during the pandemic, but the Ministry of Education promised schools to reduce the administrative load after reopening and therefore cancelled these plans. The assumption is that inspection under the regular framework will resume in January 2021, but uncertain how these will be implemented (either remotely or on-site). |

| Wales |

In Wales, the normal cycle of inspection would already be suspended as part of the curriculum reform from September 2020 for a year with instead visits to support schools in the implementation of the new curriculum. This has allowed Estyn to be flexible and agile in repurposing their work in response to the pandemic. Wales also has implemented emergency legislation, the ‘COVID-19 Act’, which allows government to make changes to regulation. These will likely include a relaxation of legislation around curriculum, testing, and reporting to allow schools the space to develop blended learning for at least another academic year and possibly longer. There are no expected changes to inspection legislation as the current standards for inspection (‘well-being’, ‘leadership’, ‘provision’) are sufficiently broad to allow for relevant inspections during and post-COVID. The recent removal of grades, as part of the wider reform agenda, also allows Estyn to understand better how schools are dealing with the crisis, how they are delivering education and how successful that is, in a more supportive manner. Engagement phone calls/visits:

There are limitations of engagement phone/video calls of 45 minutes is that only contact is made with head teacher (and sometimes analysis of documents), with limited triangulation. This is for practicality reasons as it is difficult to reach teachers and parents. Teachers are working from home and are many are also homeschooling their own children so Estyn didn’t think it appropriate to contact them at this stage., Schools will partially reopen on the 29th of June and Estyn will then slowly move from engagement calls to engagement visits of 1 inspector to 1 school, including conversations with teachers and learners. Plans have to be flexible in response to how the pandemic evolves. Estyn has increased its stakeholder engagement with local authorities and local school improvement partners to monitor how they are supporting schools in managing wellbeing and blended learning. Regular meetings are also scheduled with head teacher unions and teacher professional organizations to understand the views of teachers and the challenges they face during the current crisis To understand views and concerns of parents, Estyn set up an internal working group of around 12 members of staff who are parents home-schooling their children; they discuss challenges and benefits of the current situation. Estyn has carefully constructed a communication strategy to share the (support/ engagement) purpose of calls and visits (e.g. video messages by the Chief inspector on YouTube) and share best practice through the stakeholder groups. The communication strategy aims to share the improvement and support purpose of Estyn and provide clarity with regard to engagement visits and future inspection plans. Part of this strategy is also professional learning of all inspectors focused on ensuring a positive tone of voice with schools, how to engage with schools to support them. Estyn will not cold call schools, HMI will always first introduce him/herself on email before calling. Estyn is implementing professional development for inspectors on blended/remote learning, sharing research on potentially effective models of blended learning so inspectors are prepared for conversations with head teachers. Links (presented at the webinar): A learning inspectorate: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/document/learning-inspectorate-independent-review-estyn Transition year: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/learning-inspectorate-faqs Engagement visits explained: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/inspection/learning-inspectorate-listening-learning-and-changing-together/engagement-visits Head teacher reference group: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/sites/www.estyn.gov.wales/files/documents/Headteacher%20Reference%20Group%20app%20pack%20-%20en.pdf Advice on continuity of learning: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/about-us/supporting-continuity-learning-children-and-young-people Messages from the chief inspector: https://www.estyn.gov.wales/news/estyn-inspections-and-other-visits-suspended-support-providers-and-reduce-pressure-%E2%80%93-covid-19; https://www.estyn.gov.wales/blog/our-support-welsh-education-and-training-current-climate

|

|

| England | Focus on liaison |

Inspections were suspended by the Secretary of state in March 2020; Ofsted only goes into schools when safeguarding issues are raised or if there are concerns over serious break down in leadership and management of the school, but no cases yet (17 June 2020). Ofsted’s regular inspection purpose and method is to assess and report with a graded assessment and the intention is to go back to the normal framework after the current ‘interim period’ as this framework as these are the standards Ofsted wants schools to focus on, given that they are underpinned by research and inform school improvement. In this ‘interim period’, including the autumn period when schools (partially) reopen there are no graded assessments. Ofsted instead tries to support the system by, when resuming inspection in the autumn, answering the question of how well the school system is getting back on its feet. Ofsted is currently developing the (research) questions inspectors (perhaps joined by HMI) will use when going into schools. In the autumn the public reporting of individual schools (on these questions) will likely be in a more concise format to message to parents that Ofsted is ‘out there’, but no assessment/reporting on student outcomes or progress. Insights from individual school visits will be aggregated into a national report with the purpose of identifying ‘blockages’ that prevent schools from going back to full schooling either at the regional or national level; informing national government to address these and/or identifying effective practices of blended home-schooling/in-school learning. |

Appendix 2. Outstanding questions

| Country | Outstanding questions |

| Netherlands |

Early warning analyses informs regular (risk-based) inspection of schools and school boards. These models include data from standardized assessments of student outcomes which is now missing. The traditional method of risk analysis is also considered irrelevant in a pandemic. How to plan future risk-based inspections? How to assess student outcomes when data on achievement is lacking? Do we need to rethink what constitutes ‘risks’ of poor educational quality? The Dutch Inspectorate normally also has a regular cycle of board/school inspections every 1 and 4 years (sample of no risk boards and schools). These inspections will resume after the summer in a shortened format with no graded assessment; the framework still needs to be developed. |

| Germany (Hamburg) | In normal inspections students, parents and teachers are also surveyed, but how to interpret the data and is a comparison even possible with previous survey results? Do we need to include control items to ask about whether some aspects of education have changed as a result of COVID-19? E.g. the cooperation between teachers and whether that has improved as a result of the pandemic and the need for more cooperation. the results of these items will probably only go to schools. not enough data on pre Covid to make some comparisons. |

| Chile | How to generate ‘best practice’ from the phone/video calls with schools and share these more widely (e.g. on schools using radio to facilitate remote learning where internet access is poor)? |

| Scotland | Unsure how long blended learning will continue and Inspectorate needs to be responsive to the development of these models. Teachers are planning for examinations in 2021. If there are no examinations than teaching needs to change, but how? How will inspection needs to respond to these changes (being both agile but also making well-informed decisions) How do we monitor the quality of online learning? How to inspect remotely? These are now the big questions for Education Scotland. A number of students are not engaging in online/remote/blended learning; how to teach these students to regulate their own learning, become motivated? How to support engagement when these students go back to schools? Inspection will be suspended until it is safe to go into schools (no date determined), but questions on what inspections will then look like. E.g. can attainment be measured and how, given that students have spent so much time away from the classroom? Ideas currently discussed to do an ‘equity audit’ (pushed by IS, the main teacher union and discussed in the education committee). There are many stakeholders who are supporting schools (local authorities, school improvement partners): what difference can inspectors make that others in the system can’t or don’t? And how to find the balance between inspect, support and improve and what difference can Education Scotland make? |

| Wales | Estyn will resume regular inspection from September 2021, using the framework that was developed as part of the curriculum reform. This framework was under development when the pandemic started and might have to be adapted as schools have to focus on implementing remote/blended learning and rather than focusing solely on the new curriculum. Estyn expects to have to use a softer landing/approach in reintroducing the new inspection framework; this will follow an already introduced lower stakes approach with no summative grading and strong links between internal and external evaluation and ensure inspection is a learning experience for schools and their inspectors. Estyn is considering how to strengthen the liaison/interaction with parents when they are now home-schooling their children and will continue to do so to some degree when blended modes are put in place for the next academic year. Currently parents contribute their views on the school through surveys and meetings with the inspection team. However, attendance at the parents’ meeting varies. |

| Mexico | Need to rethink inspection activities, particularly also to understand the impact of the pandemic. Parents are not home-schooling their learners (no time, don’t think it’s their role), and teachers also argue that this is not the role of parents. Inspection perhaps needs to supervise the technology platforms where online teaching is offered, otherwise the inspection model cannot survive. |

| Belgium | How to recommence inspection in the autumn and what to evaluate then? |

See also information for:

Most recent blogs:

How LEARN! supports primary and secondary schools in mapping social-emotional functioning and well-being for the school scan of the National Education Program

Jun 28, 2021

Extra support, catch-up programmes, learning delays, these have now become common terms in...

Conference ‘Increasing educational opportunities in the wake of Covid-19’

Jun 21, 2021

Covid-19 has an enormous impact on education. This has led to an increased interest in how recent...

Educational opportunities in the wake of COVID-19: webinars now available on Youtube

Jun 17, 2021

On the 9th of June LEARN! and Educationlab organized an online conference about...

Homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Parental experiences, risk and resilience

Apr 1, 2021

Lockdown measures and school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic meant that families with...

Catch-up and support programmes in primary and secondary education

Mar 1, 2021

The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) provides funding in three application rounds...

Home education with adaptive practice software: gains instead of losses?

Jan 26, 2021

As schools all over Europe remain shuttered for the second time this winter because of the Covid...