COVID-19: do we need to redefine practices for school inspections?

4 Nov 2020 | Professionals

Abstract

This paper presents the findings from a webinar with 17 colleagues from Inspectorates of Education from 8 countries, discussing the question: do we need to redefine practices for school inspections in response to the pandemic? Delegates shared new practices that had been, or were intended to be, implemented in their jurisdictions with the purpose of: (a) producing evidence to evaluate schools’ quality and pupils’ growth, (b) identifying evidence available in the system that could be used to inform school quality, and (c) meeting the evolving needs of schools as well as of inspectors themselves. Examples of changed practice that were discussed included

- Virtual and blended inspection practices

- Judging the quality of online and blended learning

- Innovative practices to address missing data due to the cancellation of exams and on-site visits

- Engaging with parents and students

Across the four themes, inspection colleagues talked about how and why inspection practices are strengthening collaboration and the type of new skills and capacities which are needed to adapt to the changes in schools and education systems.

Prof. Montecinos (carmen.montecinos@pucv.cl)

Prof. Ehren

Prof. Chapman (Chris.Chapman@glasgow.ac.uk)

04.11.2020

Please cite as:

Montecinos, C., Ehren, M. C. M., and Chapman, C. (October 2020). COVID-19: do we need to redefine practices for school inspections? ICSEI internal report.

Introduction

School closure, the cancelation of on-site school inspections and of standardized summative assessments, have impacted the work of Inspectorates of Education worldwide. ICSEI’s Crisis Response in Education Network has addressed this impact through a series of three webinars involving delegates from Inspectorates of Education around the world.

In the first webinar, held June 2020, the focus was on examining if Inspectorates should ‘inspect’ schools and for what purpose[1]. At a time of school closures and partial re-openings in which students were engaged in online and blended teaching and learning, delegates affirmed that Inspectorates should continue serving the system. Their organizations have a unique set of skills to gather information on the challenges schools were facing, to provide schools with support and improvement tools and practices as well as to act as a ‘liaison’ agent among schools and between schools and policymakers. The purpose of control and assurance of compliance was seen as not helpful at this point, notwithstanding Inspectorates needed to address issues in schools evidencing high risk in their response to the pandemic. With some variations among countries, governments had recognized the value added by Inspectorates and relied on them to develop a better understanding of the new demands for policymakers and practitioners.

The second webinar, held August 2020, addressed if and how these shifts on the relative weight now afforded to the different purposes for inspection entailed changes in the priorities for inspection[2]. As some school systems were reopening, delegates identified areas in which support and liaison activities seemed most critical in the short-term, including: assessing quality in blended learning, defining and understanding learning loss (particularly for vulnerable children), and the consideration of other evidence and methods for evaluating school quality beyond ‘traditional’ assessment data. The use of grading was not considered appropriate as it placed additional pressure on the school community and data typically used were not available after inspection visits and standardized assessments had been cancelled. The second webinar explored the short and long-term priorities for different systems. Priorities differed by country, largely as a function of the inspection model used, legislative frameworks, and the maturity of the regime in place. There was concern that adding changes to a new system would create more disruption and stress, as well as increasing risk when changes lacked underpinning evidence.

After examining shifts in purposes and priorities, a third webinar was held September 2020 to address the following overarching question: do we need to redefine practices for school inspections? Delegates shared new practices that had been, or were intended to be, implemented in their jurisdictions with the purpose of: (a) producing evidence to evaluate schools’ quality and pupils’ growth, (b) identifying evidence available in the system that could be used to inform school quality, and (c) meeting the evolving needs of schools as well as of inspectors themselves.

The discussion in the third session was foregrounded by a presentation by Graham Donaldson who argued that inspection is a polysemantic term and an evolving practice that is shaped and molded in different ways in different contexts and for different purposes: it can be an enforcer, an assurer, it can help set policy agenda, and it can be a mechanism for creating spaces for innovation. This latter, he noted, could become increasingly important as the approval by an Inspectorate of changes in teaching and learning (e.g. using online platforms) can legitimize such innovations for parents, and ensure that schools develop new practices to meet emergent demands. Gino Cortez and Valentina Zegers from the Educational Quality Agency in Chile provided an example of how Inspectorates can learn and develop new practices to create such spaces for innovation. As noted by Donaldson, inspectors’ credibility rests largely on their understanding of the context. These three webinars illustrate that making judgements about ‘quality of education’ entails adjusting purposes and practices to respond to new priorities in a particular policy context.

What inspection practices are emerging, reinforced and questioned?

School closures, coupled with the need to maintain safety measures, has largely moved school inspection visits to virtual, and increasingly blended modes either for the short-term or, in some jurisdictions, for the long-term. School cancelations have precluded the availability of evidence typically used to judge the quality of lessons and track progress and growth on individual pupils. The wide-spread adoption of online and blended modes for delivering teaching and learning have created the need to consider new indicators and new sources of evidence to determine what “good” looks like. The emotional toll of the pandemic on students’, families’ and educators’ well-being has highlighted the broader outcomes that are expected from formal schooling and the need to include these aspects in the inspection process. Inequities in educational opportunities have been exacerbated in some countries, creating a moral imperative among inspection agencies to monitor the experiences of vulnerable students so policy and schools can properly remove barriers.

These issues have raised important challenges for inspectors’ practices in terms of the activities they undertake to fulfill their purposes and in their relationships with educators, parents, students and boards. Additionally, Inspectorates’ decisions to focus their work largely on support functions has also raised questions about the skill set needed by inspectors as schools navigate uncharted waters and negotiate the provision of quality education. To what extent can inspectors, who themselves have not led schools in a pandemic provide credible advice to school practitioners and boards?

These issues and, particularly, the following questions were discussed with 17 delegates from 8 countries (see Table 1).

- Which data is missing to evaluate school quality, given the suspension/cancellation of exams and suspension of inspection visits?

- What new practices and alternative data sources have been, or will be, introduced to evaluate schools and pupils?

- Do other actors in the system hold relevant data that could inform school inspections in your country?

Table 1. Webinar participants

| Country | Role Represented |

| Belgium | Educational inspector primary schools, Flemish Inspectorate |

| Belgium – Flanders | Inspector – Development Officer, Flemish Inspectorate – SICI |

| Canada | Executive Director, ICSEI |

| Chile | Chief of the Evaluation and Performance Orientation, Educational Quality Agency |

| Chile | Head Department of International Studies, Educational Quality Agency |

| Chile | Professor, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso |

| Chile | Assistant to the Director, Educational Quality Agency |

| Malta | Education Officer, Quality Assurance Department |

| Malta | Director, Directorate for Quality and Standards in Education |

| Netherlands | Professor, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam |

| Netherlands | Coordinator international affairs, Dutch Inspectorate of education |

| Netherlands | Data scientist, Dutch Inspectorate |

| Scotland | HMI, Education Scotland |

| Scotland | Professor, University of Glasgow |

| Scotland | Professor, University of Glasgow |

| Scotland | HMI, Head of Scrutiny Education Scotland |

| Wales | Assistant Director, Estyn |

The summary of these discussions is organized around the following:

- Virtual and blended inspection practices

- Judging the quality of online and blended learning

- Innovative practices to address missing data due to the cancellation of exams and on-site visits

- Engaging with parents and students

There are two additional themes that run across issues just mentioned:

- How and why inspection practices are strengthening collaboration

- What new skills and capacities are being required by an Inspectorate that is adaptable to the new demands addressed in the previous topics

Virtual and blended inspection practices

A shift in practice across countries has been the introduction of virtual inspection visits with the plan to implement a blended model of inspection (e.g. do all interviews online with a shorter on-site visit to observe in-school teaching and have a final feedback meeting). After an initial period of adjustments and planning, in most of the countries represented at the webinar, Inspectorates resumed school visits through virtual meetings (Chile, Scotland, Wales, Netherlands). These meetings had the purpose of establishing a connection with schools, inquiring about their challenges as well as identifying areas in need of support. The tone of these meetings was largely collaborative, providing support and emotional containment as school leaders encountered difficulties, tracked students and families who were not connecting and organized staff to work remotely.

In some countries virtual inspection visits have been accompanied with a more focused examination of the dimensions and indicators addressed in the national inspection framework. There is a trend to increase in depth and reduce the breath of school inspection. In Chile, for example, from a total of 83 indicators, the Agency will now focus on 29 with particular attention to teaching and learning, shortening the visit to two days.

In Malta, the Inspectorate has submitted a first draft for visiting schools after reopening, which included a description of three foci for inspection visits (the term ‘inspection’ is not used, but ‘visit’): a) health and safety guidelines and how schools are planning to mitigate infection spread, b) the curriculum and which subjects/ content the school is prioritizing and c) how the school is ensuring that every student is receiving education, either online/blended or in school. The visit would be two days, with the first day including an online meeting with the school head and the COVID-liaison officer of the school.

In the Netherlands, the inspection framework has three types of inspections: a national monitor of educational quality, quadrennial (risk-based) inspections of school boards and a sample of their schools and theme inspections. It is legally set that that all schools in the Netherlands need to be visited once every four years. During the period of school closures, most visits were suspended or done online for schools and school boards identified as high risk of failing quality in last year’s early warning models or for schools that needed to be inspected under the four-year timeframe for inspection. Over the next month, there will be an effort to move to on-site school visits.

In Wales, schools have reopened and the Inspectorate is having virtual meetings with schools to learn about their experiences. The hope is that physical visits can restart in November 2020, but only when considered safe and appropriate. The focus of these virtual meetings has also been on helping schools self-assess their blended learning model. Schools that have been contacted are very keen in talking about their experiences and want to know how other schools are addressing the new demands placed by the pandemic, positioning inspectors in a pollination role.

How to judge the quality of online and blended learning?

The pandemic has changed some of the fundamentals of the educational context in introducing online teaching and blended modes of online and in-school learning. As of yet, there is little solid understanding of what “good” looks like, creating a high level of uncertainty for inspectors and schools alike. Additional challenges for Inspectorates include how to capture the quality of student-teacher interactions through online visits, where quality of teaching would normally be assessed through direct observations.

All delegates agreed that tools to assess the quality of blended learning are currently not available. This is an important gap given the dynamic nature of school closures and re-openings, creating the need to offer blended learning to safeguard physical distancing. When families opt out of in-school classes their students will be participating only through online classes.

Delegates explained that their Inspectorates are considering how existing indicators can be applied to online/blended learning (thinking about evidence of what ‘engagement’ or ‘checking for student understanding’, for example, looks like in an online environment). In Scotland, the framework for ‘thematic inspections’ could be used to develop an understanding of the provision and quality of such teaching approaches, as the standards for thematic inspections are flexible and designed specifically for the investigation of the particularly theme, allowing an examination of how digital pedagogies have changed with COVID.

Delegates also discussed how inspectors could ‘observe’ the quality of online teaching, such as by logging in to the online teaching environment of a school to observe and evaluate a live online lesson. The inspector would then also talk to the teacher about how he/she has been planning that lesson and do a focus group with students to understand if the online/blended model is working for them. A key challenge in such digitized approaches to inspection, however, is to evaluate the engagement of students in online teaching as their logging and accessing teaching is a poor indicator of engagement, and engagement is difficult to observe online.

Addressing missing data due to the cancellation of exams and on-site visits

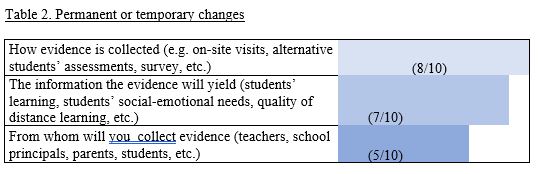

In a poll, we asked delegates whether in the upcoming year their Inspectorate would return to the general framework and proceed as they had been conducting their work previous COVOD 19. Responses from 10 participants from 6 countries (ICSEI webinar 16 September 2020) show that some Inspectorates of Education have not continued with business as usual. What has changed is presented in Table 2, with most making changes on how evidence is collected and the kinds of information they plan to examine. Some are planning on making changes to the sources of evidence in terms of the range of stakeholders consulted.

In Chile, Canada and the Netherlands all or some exams were cancelled. In Scotland the only standardized central exam for age groups 15-17 was cancelled this year and it is not clear how the Inspectorate will address this gap in having credible data for next year (including the grade inflation caused by replacing this with teacher prediction). The Scottish Inspectorate is considering looking at progress of students instead of attainment; e.g. looking at where students turn up in their later school career or comparing multiple time points of individual students over time to understand their progress. Furthermore, in Scotland the exam diet has been cancelled for National 5 (15-year-old) examinations in 2021 and students will be allocated grades based on teacher estimation based on 2-4 pieces of evidence.

The legitimacy of centralized exams (including as part of a measure of school quality) has been called into question in a number of countries given their limited predictive value for students’ later school career as well as actual learning (Scotland, Chile). In Scotland, for example, the cancellation of this year’s exams has led to a discussion about whether a different system is needed to measure student learning, particularly as evidence suggests that students who haven’t done well in school exams can be highly successful in college or university later on. Also, the cancellation of exams as well as replacing these with school-based assessments have been highly controversial with much higher pass rates for various subjects. Questions are being raised about how this information is related to developing a better understanding of school quality.

In Chile, the Educational Quality Agency has developed new comprehensive learning assessments in mathematics, reading and well-being for all grade levels. Schools use them on a voluntary basis and results have no consequences for the school’s categorization in the quality ratings; tests are available online and schools get immediate results. Through this approach, schools and the Agency can measure how much students are learning and estimate learning loss. The intention is to help teachers assess student progress, who according to the national teacher evaluation system tend to have weak assessment skills.

In the Netherlands missing data due to the cancellation of exams, will impact the risk models, but not to a great extent, as these only represent 10%-20% of the scores. Overall there is still enough data available to make a risk assessment (i.e., student enrollment, teacher sick leave, among others). The absence of test data, however, is likely to have an impact on the assessment of school quality and the use of data for instructional purposes because missing data is likely to limit the prediction of individual students’ learning trajectories; information which is often also shared and discussed with parents, especially with regard to choices about future education.

Engaging with parents and students

Parents are responding in different ways to the reopening of schools. Some parents are keen to get their children back into schools, while others are reluctant and fearful preferring to keep their children at home. This raises questions about how to judge the quality of students’ learning when some are receiving face-to-face teaching, while others continue online. An additional challenge are short-term absences from in-school learning as some groups of students return to distance learning as systems experience cluster outbreaks of COVID-19 while others continue with face-to-face learning.

In Malta, for example, a major concern was that students would not return to school when they reopened in September. In Chile, polls show that over 80% of the parents do not want schools to reopen in 2020. There is sympathy for parents who want to keep children home if they have a health condition. These children cannot be encouraged to come back. In Wales attendance is not obligatory but it is encouraged and schools work with parents to overcome their fears. Schools are expected to provide distance education for families who opt out, but there is a workload issue as about 90% are attending. For the 10% opting to be on distance education, education consortiums are considering the development of resources to be shared among schools.

In several countries, governments, in some cases through their Inspectorates, have conducted surveys with parents and students. In Chile, for example, more than 38,000 people responded to a survey asking for the meaning of quality education. In Canada the Ontario district has been actively contacting families and undertaking surveys to assess student experience, and to understand the choices they are making in terms of the mode of schooling available. Engaging parents, teachers and children in inspection is also important for the Scottish Inspectorate, particularly if the country goes back into lock down.

Inspection practices that promote collaboration

As Inspectorates address the problems outlined above, collaboration has become key. As schools create local solutions to share problems, Inspectorates can play a key role in fostering collaboration and learning across schools. In Scotland and Chile, for example, Inspectorates have facilitated school-to-school learning by creating virtual meetings for schools to share promising practices. In other countries (i.e., the Netherlands), however, this is not possible as the law precludes inspectors from sharing information from individual schools and the responsibility for improvement is specifically outside of the Inspectorate’s remit.

In response to the challenge of defining ‘good blended learning’, collaborating with teachers who have been implementing this model can be quite helpful. In Scotland the inspection process includes local assessors (mostly serving school principals) who are part of the inspection team and bring practitioners’ knowledge and perspectives to the inspection process. As many Inspectorates have not worked in schools during COVID-19, the first-hand experience of these assessors provides relevant insights. The involvement of local assessors also builds capacity for system leadership.

The collaborative approach based on professional dialogue is particularly appropriate to support innovation. In Scotland a needs-driven system is implemented to support schools; the system allows for co-design, collaboration and co-construction between schools and inspectors regarding the focus of the support to be provided by the Inspectorate. This also involves strengthening the connection and collaboration with Scotland’s improvement agency. In Chile, the online orientation visits developed at the start of the pandemic resulted in a more participative approach to inspection. Schools can now choose one of the two dimensions for a focused visit. The final report, based on collaborative reflective conversations between the inspectors and the school leadership team, provides an overview of strengths and weakness.

The learning Inspectorate

These changes in practice entail developing new capacities at the system level (Inspectorates) and at the inspector level- for judging quality. Moving to online inspection, as well as blended learning has left some inspectors feeling deskilled (Chile, Wales, Netherlands, Scotland, and Malta). The new context challenges inspectors to learn and develop to continue to foster learning across schools. The credibility of inspectors in the view of schools and wider stakeholders is premised on their authority and knowledge of quality of practices. The absence of inspections in many systems, combined with the ‘distance’ that some Inspectorates have been perceived to have during the pandemic poses a challenge to maintaining credibility within some systems. This situation, combined with localized responses and a focus on local reflection and self-evaluation may compound the situation in some systems.

In Malta, the Agency has, for example, contracted with a local university to offer online classes for inspectors about online teaching and learning. Inspectors here expressed a lack of confidence in their ability to make judgments about quality of online instruction and offer support to schools as these tackle new challenges in response to the pandemic. The Netherlands is also `providing professional development related to online learning and teaching. In Wales, additional learning opportunities will be sought from teachers who are engaged in blended learning as well other HMI’s departments (i.e., IT and school improvement services). A few inspectors are uncomfortable with trying to evaluate a school’s blended learning offer until they have a deeper knowledge of the different models of blended learning.

A major concern expressed across many of the Inspectorates participating in this webinar was that without the appropriate skill set, inspectors’ credibility is compromised. To date, inspectors’ expertise is fit for purpose in evaluating school quality in ordinary times. Currently, in many systems expertise in supporting schools through the pandemic is limited. Some of the major challenges facing Inspectorates are related to developing a common understanding and shared set of expectations about evaluating the quality of online and blended learning and teaching and assessing the extent to which schools are addressing the challenges associated with potential learning loss and rising inequities as we move through the pandemic.

| Country | Key issues of practice |

| Wales |

Inspection had been suspended during 2020 as schools were adopting a new curriculum. Many schools have reopened and the Inspectorate is having virtual meetings with schools to learn about their experiences. The expectation is that physical visits can restart in November 2020, but if it is safe and appropriate. The focus of inspectors has been on helping schools self-assess their blended learning model. Schools that have been contacted are very keen in talking about their experiences and want to know how other schools are addressing the new demands placed by the pandemic, positioning inspectors in a pollination role. The emphasis has been on collaboration as the situation is very dynamic, with schools ready to close partially or totally if COVID 19 cases are detected. Attendance is not obligatory but it is encouraged and schools work with parents to overcome their fears. Schools are expected to provide distance education for families who opt out, but there is a workload issue as about 90% are attending. For the 10% opting to be on distance education, education consortiums are considering the development of resources to be shared among schools. As the inspection visits consider the use of a virtual or a blended model, there are efforts under way to learn from the experiences of the adult education Inspectorate, which had been conducting virtual visits prior to the pandemic. Additional learning opportunities will be sought from teachers who are engaged in blended learning as well other HMI’s departments (i.e., IT and school improvement services). The goal is that across the system, there is a common understanding and shared expectations. |

| Canada |

Education is a provincial responsibility. In Ontario the Educational Quality and Accountability unit creates and administers standardized assessments to measure Ontario students’ achievement in reading, writing and math in grades 3, 6, 9 and 10. For the 2019-2020 year, assessments were cancelled and they might be cancelled again for the 2020-2021 academic year. Grade 10 literacy test, a requirement for graduation, was waived. Beyond these state assessments, schools and school boards have capacity to collect a wide range of data, including SEL and learning skills, used for planning. All of the school and district level assessments are being done online. After schools were reopened, about 30% of the students have opted for online learning due to families’ concerns with maintaining physical distance. The Ontario district has been actively contacting families and doing surveys to find out how students are doing and address parents’ concerns about the choices they have to make in terms of the modes of schooling available. Survey reports are provided to schools, students and families but they are not available for the wider public. Over the last years, universities and schools have conducted much work on collaborative research and data-driven decision-making and this provides alternative evidence sources. |

| Netherlands |

What data are missing for school evaluation varies by the education sector addressed. High schools and primary schools standardized examinations were cancelled. These are used to make judgments about schools’ quality, for the allocation of students when moving from primary into secondary schools and for predicting students’ learning trajectories when they enter secondary education. Secondary school standardized tests for different subjects will also be missing. These missing data, however, will not greatly impact the risk model as these only represent 10%-20% of the score. Overall there is still enough data to make some estimates of risk (i.e., changes in enrolment, amount of sick leave, among other indicators). A mayor concern is with vocational education because students cannot access internships. There are several organizations that have data and or support schools, but there are important legal restrictions in terms of providing that data to the Inspectorate. Schools have relevant data that could be used but due to privacy issues these cannot be shared with the Inspectorate. There are no plans to use data collected by other actors within the system and also there is no need to do so. The inspection framework has three types of inspections: a national monitor of educational quality, quadrennial (risk-based) inspections of school boards and a sample of their schools and theme inspections. On site-school visits have been suspended for most, but a few schools were visited which were judged to be most at risk. By law, the inspectors must be on-site at each school every four years and that has been addressed through online visits. Theme inspections have been only online. Currently, a blended inspection model is being used with at risk schools: physical visits, taking social distance precautions, as well as virtual meetings. Quality of online education is hard to judge because the inspectors do not know what quality online education looks like at the moment. What is a good online lesson? There is a need to build this competence and the Dutch inspectorate is doing research out how to assess the quality of online education. The law specifies which documents and data must be produced by school boards and provided to the Inspectorate. Boards have developed or contracted software to assess individual pupils but the Inspectorate cannot access such data. The data that has been collected as part of the national COVID-monitor cannot be used for risk-models since schools and school boards have been told that the survey would not be used for this purpose (in order to stimulate transparency). A poll conducted with school leaders asked about students with whom the school lost contact or finding the good connectivity, with the vast majority of the students receiving lesson online when schools were closed. Some students dropped out (concentrating in low SES and special needs groups). Another finding was that the number of hours students spent on learning activities was a concern and most school leaders thought that the quality of learning was below par. The Ministry of Education is doing a survey with parents on how well the education at home is going. |

| Chile |

The school year in Chile goes from March- December. Due to the pandemic, schools have been closed since March 2020. Standardized assessments were cancelled as well as school visits. A mayor concern during this period of distance education is that many students do not have internet connection in their homes. For this period of school closures, the Agency developed a stage approach to work with schools, focusing largely on support[3]. The first stage involved school mentoring, in the second stage online visits were conducted, identifying promising practice and a survey was sent to parents to learn how they characterize quality education. Additionally, a set of comprehensive learning assessments was developed for teachers’ usage. The third stage will involve blended school visits, after schools reopen. Mentoring for school leadership teams. After school closed, the Agency decided to make their inspectors available to support schools. The mentoring process included three meetings with the aim of empowering school leadership teams and increasing their sense of efficacy as they developed a response to educating children through distance education. The first meeting involved an inquiry into how schools were doing, their difficulties and the emotional well-being of staff. Schools identified an area on which they wanted to work with the Agency. In the second session, the inspectors (evaluators) offered target supports and were provided with some resources. A third, follow-up session, inquired into how and with what efficacy schools used the resources made available in session two. Additionally, they identified other promising practices that schools had developed locally. Stage two, sharing promising practice through the webpage. Through the mentoring process evaluators identified promising practices that various schools had developed as they learn to work remotely with staff and students. The 70 practices identified were systematized into cards that were shared with all schools through the Agency’s website. The practices selected were those that addressed a specific difficulty the school had encountered. Stage two, networking to share promising practices. Schools that had developed these practices were invited to meet, virtually, with three other schools facing similar difficulties, thus creating a learning network. In the first session, the school shares the experience and the other schools reflect on how they can use this practice in their local context. In the second session, evaluators meet individually with each school to support implementation. In the third session, schools meet to discuss and reflect on their use, adaptations and effectiveness of the practice for addressing the targeted problem and what can be improved. The aim is to create problem-solving capacity at each school, not to copy practices that have worked in other contexts and to strengthen school-to -schools support. This approach is also more efficient as two inspectors work with four schools simultaneously, as opposed to with one school at a time. Stage two, changes to the orientation for online visits. The Agency decided to apply what had been learned from the two previous activities to make some structural changes to how school visits will be conducted moving forward. These changes include a re-design of the visit through a collaborative process with the participation of inspectors (evaluators), involving a shorter visit focusing on fewer standards (from 83 to 29), to examine two dimensions: teaching and learning and second that is chosen by the school. The visit still follows an expert model, with the inspectors having the expertise, but now the final report in which strengths and weakness are identified is written as a result of a collaborative reflective conversation between the inspectors and the school leadership team. The aim is to prepare a report that makes sense to the school and provides more resources. Stage two, parent survey. The Agency lacks a clear definition and criteria to judge the quality of distance education. To address this knowledge gap, a survey was developed asking various stakeholders what characterizes quality education during this period of distance education. They have received 38,000 responses, with a majority coming from parents, about a fifth from educators and few from students and other stakeholders. Preliminary findings show that overall parents are satisfied with their students’ learning experiences, though not all agree. For respondents, quality education must focus on academic learning and social-emotional skills. Stage two, development of a new comprehensive learning assessment in mathematics, reading and well-being for all grade levels. Schools use these assessments on a voluntary basis, are available online and schools get immediate results. Results have no consequences for the Agency’s evaluation of the school. |

| Malta |

Malta was experiencing a spike in infections at the time this webinar took place. Schools were expected to open on the 28th of September, but the two teacher unions have issued a statement calling to not open schools; this is a reversal from a previous agreement with government to prepare the reopening of schools. Union members are concerned about schools not being ready for reopening, such as not having a COVID coordinator in place, not having sufficient space for physical distancing or plans to teach smaller classes to allow for physical distancing. Both on-site or virtual inspection visits are not currently in place and moving forward with these visits requires negotiating with the union. Inspectors are not allowed to go from one school to another. There are concerns that virtual school visits lead to missing the observation of classroom practices. Discussions are under way on how to continue the work and an alternative being discussed is to go for greater depth instead of breath. One particular issue for in-depth examination is digital teaching and learning. Schools are being encouraged to focus and prioritize, to not evaluate everything, but to focus on the use of digital technology of teaching and learning. The Inspectorate submitted a first draft for visiting schools after reopening, which included a description of three foci for inspection visits (the term ‘inspection’ is not used, but ‘visit’): 1) health and safety guidelines and how schools are planning to mitigate infection spread, and 2) the curriculum and which subjects/ content the school is prioritizing and 3) how the school is ensuring that every child is receiving education, either online/blended or in school. The visit would be 2 days, with the first day including an online meeting with the school head and the COVID-liaison officer of the school. Not all schools, however, have a liaison officer in place, which is one of the arguments of the teacher unions to oppose the reopening of schools. The school leader would be asked to send a questionnaire to stakeholders about how the school is implementing COVID measures and is addressing the different needs of students. The questionnaire aims to give a voice to a wider group of stakeholders and incorporating their views in inspections. Inspectors would visit the school on the second day, including a 2,5 observation of classes and tour of the school, trying to be as ‘invisible’ as possible. At the end of the second day the inspector would have a feedback meeting with the school head. Schools have not administered final exams and students were assessed on the basis of teacher assessments administered up until March, when schools closed. In Malta, students are now sitting for their final exams and parents are worried that this has caused the increase in infection rates. There was physical distancing in the school during exams, but students would not distance themselves from peers outside of the school building. An important concern is that inspectors feel de-skilled as they express lack of confidence in their ability to make judgments about quality and offer support to schools as these tackle new challenges in response to the pandemic. Additionally, there are concerns about students who might not return to in-school classes after schools reopen due to parents’ fear of putting their children at risk. |

| Scotland |

There are no public standardized assessments in Scotland for age groups 3-15; assessments results are not public but available to schools and the Inspectorate. Standardized central exams were cancelled in Scotland and replaced by teacher predicted grades in 2020 with additional statistical recalculation. The recalculated teacher predicted grades in 2020 (in the absence of central exams) led to widespread public uproar as students from deprived areas were less likely to receive high grades compared to students from affluent areas. As a result, the government decided to overturn the statistical recalculation and instead award grades on teacher predictions only. However, an analysis in 2019 showed that half of the teachers made incorrect predictions of the scores their students would receive on the final exams. As a result, the grades for 2020 are also likely to be incorrect and figures are showing a much higher pass rate in all subjects and widespread grade inflation. The Inspectorate may have to look at progress of students instead of attainment; e.g. looking at where students turn up in their later school career or comparing multiple time points of individual students over time to understand their progress. The cancellation of this year’s exams has led to a discussion about whether a different system is needed to measure student learning, particularly as evidence suggests that students who haven’t done well in school exams can be highly successful in college or university later on. The predictive value of the central exams is very low. Success in exams does not give accurate information on how much a student has learned in school; it only measures a very small set of skills and whether students remember facts accurately, not those skills that really matter such as collaboration, self-regulation etc. Students will forget the facts after the exam and schools are not. In Scotland school inspection has been suspended temporarily and currently they are thinking what resumption of inspection might look like. The collaborative approach based on professional dialogue is particularly appropriate to support innovation. Over the coming year the plan is for the Inspectorate to do support visits and from those visits identify support challenges for professional dialogue. These professional dialogues will enable a co-design of the support provided by the inspectors as a result of a joint decision on the supports required and the priorities. This involves strengthening connection and collaboration with Scotland’s improvement agency. The inspection process includes local assessors who are mostly practicing head teachers who join in the inspection and bring practitioners’ knowledge. As inspectors have not worked in schools during COVID, the experiences of these assessors will be very valuable. These assessors have that first-hand experience to add the inspection process. Also, by including the, more system leadership capacity is developed. Support will be provided virtually, which will lead to missing engagement with teachers, teaching and learning. A concern expressed by some is how to account for children’s voices in this process as some of the feedback show they have expressed a lack of voice. Engagement with parents, teachers and children as part of inspection is also important for the Scottish Inspectorate and something to maintain, particularly if the country goes back into lock down. There is a need to look at the learning gap due to inequalities in access to technology and the impact of COVID on increasing existing inequalities. The Inspectorate would also need to look at how schools are using technology and place a greater focus on students’ well-being. The Inspectorate needs to make greater use of teacher assessments and judgements, even though these haven’t been accurate. A key task is supporting teachers in accurately assessing students and student progress. The Scottish Inspectorate could potentially also make more use of data from other agencies, such as the qualification agency. The Inspectorate already has access to that data, such as on trends over the past five years, patterns in performance of different subgroups. The Inspectorate would also need to think about how to evaluate blended learning. The Inspectorate doesn’t really have the skills yet to evaluate the quality of online/blended learning, although the criteria may be similar; e.g. are children involved in the teaching, does the teacher check for understanding. The Inspectorate would, however, need to operationalize these criteria for an online environment, such as by thinking of how to assess what ‘checking for understanding’ looks like in an online environment. There are opportunities to digitize some of the existing approaches to inspection. Evaluating engagement of students in online/blended learning may, however, be difficult as that is difficult to observe. There is a need for teachers and inspector to look at students’ skills, particularly to self-regulate their learning (i.e. executive skills, meta-skills), collaboration and resilience. The current pandemic is an opportunity for innovation and in the special school sector where children have historically had difficult attending school the blended model seems to work well. There is a recognition that inspection cannot go back to business as usual, but as it has not been that long since the current self-evaluation tool was put into place, introducing changes might be counterproductive given all the changes brought by the pandemic. Thematic inspections are not tied to indicators but to parameters that are pertinent. Looking at teachers’ workload, for example, requires a specific methodology for gathering information specific to the theme. Therefore, when doing thematic inspections there is an opportunity to use other indicators. Thematic inspections do not report on schools, so there is an opportunity to use the thematic approach to look at, for example how digital pedagogies have changed with COVID, to what extent does the digital pedagogies continue or will they be discontinued. Another. topic could be on children´s views on post-pandemic education. |

[1] Ehren, M.C.M., Chapman, C., and Montecinos, C. (July 2020). COVID-19: do we need to reimagine the purpose of school inspections? ICSEI internal report. Available at: https://policyscotland.gla.ac.uk/covid-19-reimagining-school-inspections/

[2] Chapman, C., Ehren, M.C.M, Montecinos, C. and Weakley, S. (August 2020). COVID-19: do we need to redefine the priorities for school inspections? https://policyscotland.gla.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PSSchoolnspections-2.pdf

[3] In Chile, the term ‘inspection’ is not used, instead ‘orientation visits’ is used and inspectors are known as evaluators. The school evaluation produces a public report identifying strengths and areas for improvement, with broad orientations.

See also information for:

Most recent blogs:

How LEARN! supports primary and secondary schools in mapping social-emotional functioning and well-being for the school scan of the National Education Program

Jun 28, 2021

Extra support, catch-up programmes, learning delays, these have now become common terms in...

Conference ‘Increasing educational opportunities in the wake of Covid-19’

Jun 21, 2021

Covid-19 has an enormous impact on education. This has led to an increased interest in how recent...

Educational opportunities in the wake of COVID-19: webinars now available on Youtube

Jun 17, 2021

On the 9th of June LEARN! and Educationlab organized an online conference about...

Homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Parental experiences, risk and resilience

Apr 1, 2021

Lockdown measures and school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic meant that families with...

Catch-up and support programmes in primary and secondary education

Mar 1, 2021

The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) provides funding in three application rounds...

Home education with adaptive practice software: gains instead of losses?

Jan 26, 2021

As schools all over Europe remain shuttered for the second time this winter because of the Covid...